How a University Can Make a Change: Washoe County’s Drug Problem

Downtown Reno's iconic Landmark Arch. Photo by Bailey Ohnstad.

By Mackenzie Rankin, Lexi Cantrell, and Bailey Ohnstad

“The Biggest Little City in the World” has a legacy of larger-than-life culture and a flourishing economy that couples gambling and tourism profits with a focus on bringing new technologies and industries to Northern Nevada. Reno’s constant development, in tandem with an influx of individuals from California to the greater metropolitan area that surrounds it, including Sparks and Spanish Springs for example, yields a population of more than 500,000 individuals in Washoe County.

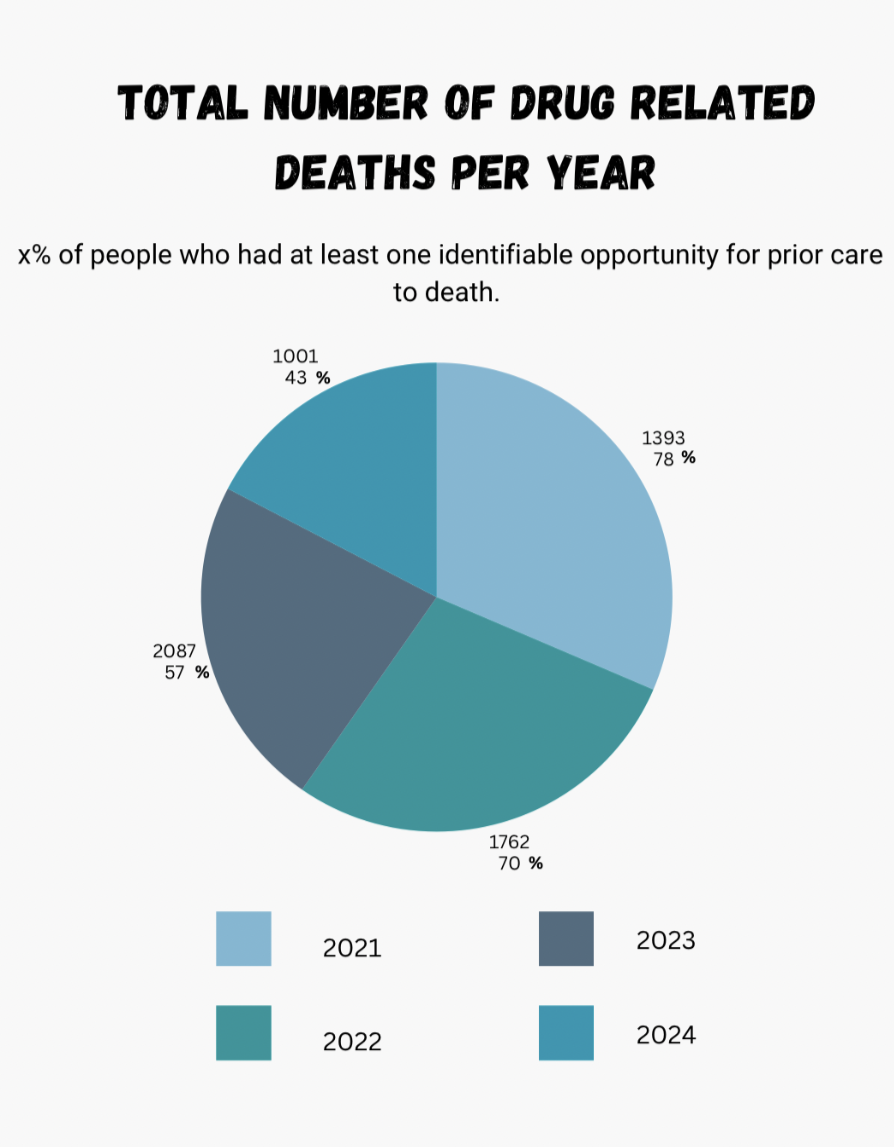

Annual Opioid Fatalities in Nevada, Data collected from NvOpiodResponse.org

While its outward appearance is one of achievement and incredible growth, Washoe County’s expansion has a seedy underbelly ripe with issues of income inequality, a lack of affordable housing, and an alarming increase in homelessness. One of the county’s biggest issues, however, is even further beneath the surface: rampant drug abuse that results in high overdose rates.

The following recent videos from Kolo 8 News show how prevalent Reno's drug problem is: https://youtu.be/Y7Na6OFRNm4

A major factor that exacerbates Washoe County’s unintentional overdose rate is the high concentration of residents living in socially vulnerable neighborhoods. People in these highly-vulnerable communities face more barriers to addiction treatment, harm-reduction services, and mental-health support, which dramatically increases fatal-overdose risks and contributes to high rates of drug abuse in Washoe County.

The Nevada Independent article “Reno has drug (overdose) problem,” describes how large the opioid crisis’ impact has been in Washoe County. From January to June 2022, Nevada recorded 424 overdose deaths (averaging less than 2 per day), and in Washoe County there were 109 deaths in that period. Opioids played a role in about 88% of those deaths.

According to a data report by the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR)’s School of Public Health, between 2021 and 2023, suspected overdose emergency-department (ED) visits in Nevada increased 24% for all drugs, and 46% for opioids, with similar patterns in Washoe County. In Washoe County, from January to June 2024 the suspected overdose ED encounter rate ranged around 28–35 per 100,000 population. 54% of ED overdose encounters were male; 46% female.

The report notes that Washoe County’s unintentional drug-overdose death rate is nearly twice that of many other counties in Nevada, including the much larger Clark County in the state’s south. This makes Reno/Washoe a high-priority area for intervention.

An organization affiliated with UNR’s School of Public Health is trying to change that. The Nevada Opioid Center of Excellence (NOCE), started within the Center for the Application of Substance Abuse Technologies (CASAT) in 2024, is trying to develop and disseminate evidence-based training models and technical assistance to providers, professionals, and community members in order to address opioid use and abuse. Compiling data via surveillance has allowed NOCE to develop a library of resources to support statewide efforts in managing opioid use.

“A lot of the work that the Center for Opioid Excellence does is for individuals in the community who are naive about a lot of these programs,” said Morgan Green, the Primary Investigator at NOC. “Just having that basic level of information and trying to ensure that all of the communities are aware of what really should be expected in terms of this field.”

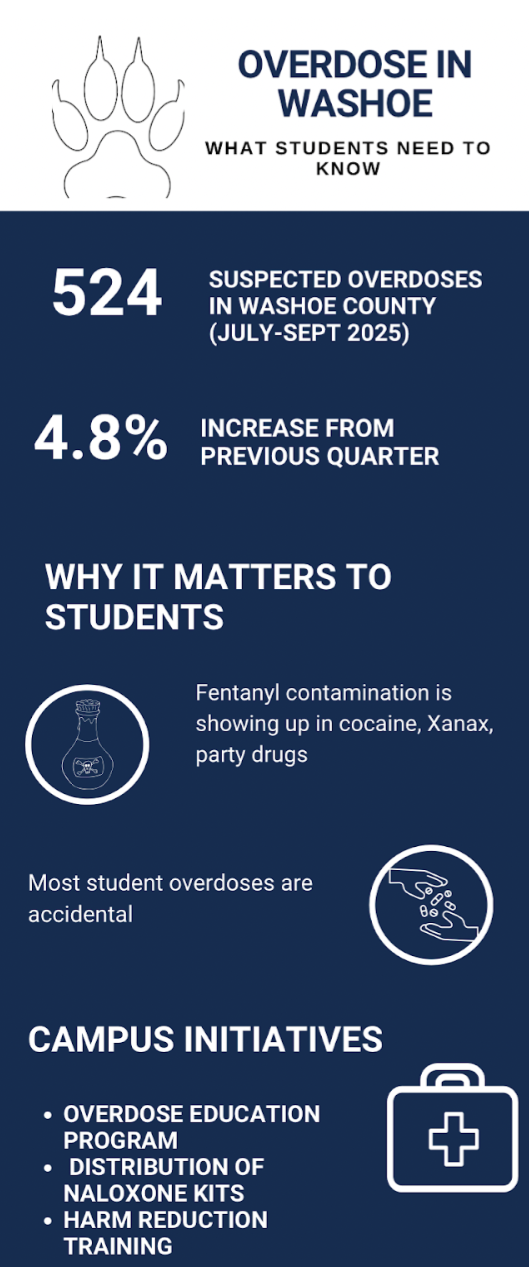

The most recent subset of overdose data compiled by NOCE between July 2025 and September 2025 identified 524 suspected drug-related overdoses in Washoe County, marking a 4.8% increase from the previous quarter. While the amount decreased minutely statewide, Washoe County’s crisis has developed into an outlier, one that has statewide implications. This is not the only time Washoe’s overdoses have resulted in standout statistics. According to the CDC a 24% decrease in national overdoses in 2024 resulted from overdose declines in 45 states. One of the 5 states to see increases was Nevada, alongside the likes of Alaska and South Dakota.

Morgan Green, the Primary Investigator for NOCE says the increase over the past year, especially in Washoe County, is more complex than what meets the eye.

“I know that there was a lot of information that came out last year in terms of Nevada being one of the five states that saw an increase of overdose deaths while we saw basically every other state see a decline,” Green said. “That’s a little misleading. We did have some high numbers at the beginning of the year, and so it kind of took away the downward trends that we had by the end of the year.”

Despite Nevada’s tendency to lag behind in drug trends, which Green says happens on both the upturn and downturn of overdose rates, the reality remains that Washoe County has a severe problem. As the problem continues to grow in complexity, however, a change is necessary to protect the state’s future: its students.

Students Are Most At Risk

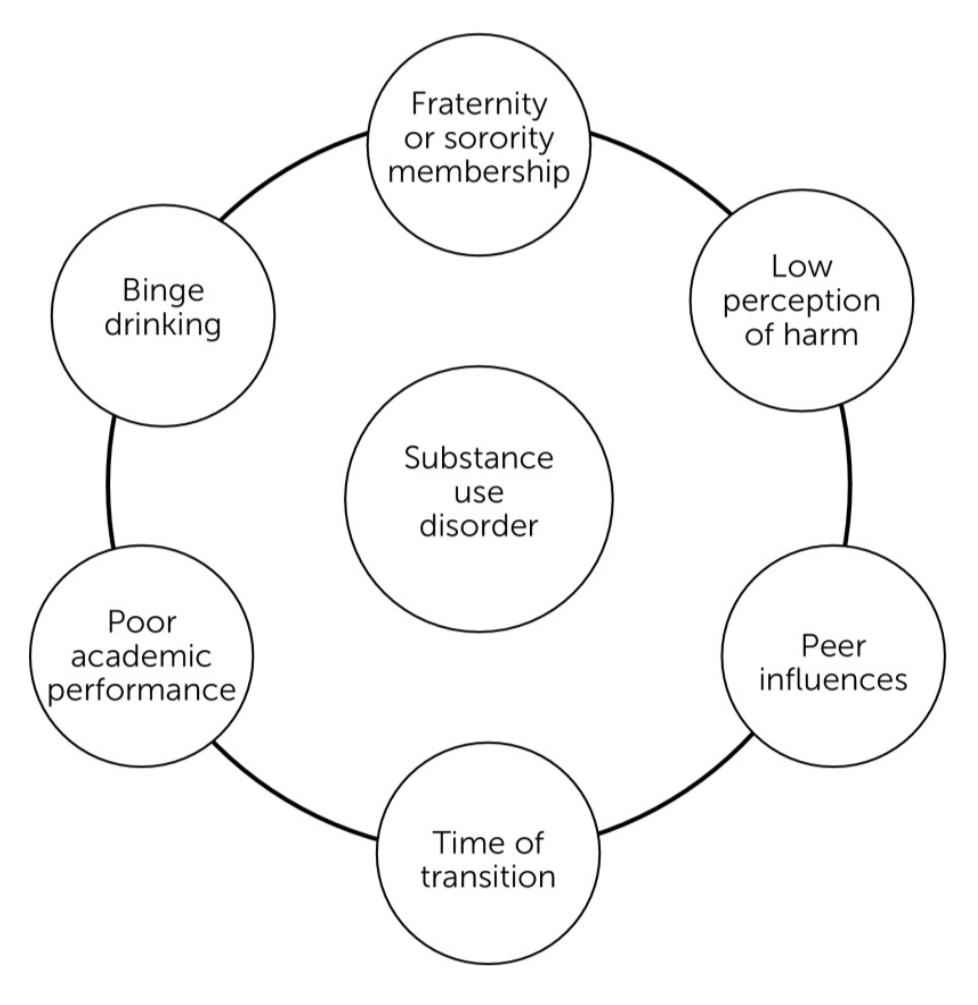

Marijuana, Ecstasy, Cocaine, and stimulant medications like Adderall are frequently associated with an all-too-familiar issue on college campuses: drug abuse. The dangers of such substances and the motivating factors for use vary, but consequences remain similar and can extend to the academic and personal lives of student users in devastating ways.

UNR, home to more than 23,000 students according to fall 2025 enrollment totals, is no stranger to this issue. According to Daniel Fred, coordinator for Nevada’s Recovery and Prevention Program (NRAP), students at the university are most commonly struggling with abuse of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. That wasn’t the case in the program’s early years.

“When we started in 2012, almost every student coming in was in recovery for opioids,” he said. “We saw a lot of students on campus who got introduced to heroin in their dorms. It's a completely different realm than now where most students are recovering from weed, coke, and alcohol.”

Risk factors associated with substance use disorder among college students. Source: National Library of Medicine, “Substance Use Among College Students”

According to the National College Health Assessment at UNR in 2024, 31.9% of students at the university reported using cannabis in the past two months. Additionally, in that same time, UNR’s University Police Department made 13 drug-related arrests including ten for methamphetamine, two for fentanyl, and one for cocaine. While much of this use is off campus and the severity of drug type has changed, a new danger has come to the forefront for users: something Fred calls “unintentional overdose”.

“The opioid overdose education has shifted to where it's more about “accidental overdose” or “unintentional”. They’re not—they’re doing coke or xanax or something like that and not opioids. So it’s education in that it’s not just opioids that could cause [overdose].”

With sharp upticks in overdose rates, the complex challenge faced by preventing overdose in all users requires reaching some of the biggest stakeholders in Nevada’s future.. Efforts on campus at UNR are seeking to do so, but not without their own obstacles.

How Can Campuses Create Change?

In 2024, an online education program for overdose prevention and intervention was launched utilizing resources from NOCE, CASAT, and the UNR School of Public Health. Malia Sanderson, a health educator at the Student Health Center described the program as a way of bridging the gap between students and access to harm reduction education.

“Students take a quick 20-minute quiz and video, learning about the medical amnesty laws here in the state of Nevada, things that we follow as healthcare providers, as well as, what it [Narcan] can or can do and what it cannot do,” she said. “And then once students have completed that little training module, they're able to either come to the student health center, to the distribution desk, at the KC, School of Public Health, Counseling Services, anywhere that they would like to pick up their free Narcan kits.”

Infographic showing overdoses recorded in Washoe County during the summer of 2025. Data from Nvopioidcoe.org

These kits are available discreetly and include two doses of naloxone (a stimulant that reverses opioid overdose), fentanyl and xylazine test strips, a CPR mask, disposable gloves, as well as other informational resources. The kits also include pamphlets displaying step-by-step instructions on administering aid to people who are experiencing an overdose. The program aims to highlight a point that is often overlooked: most accidental overdose deaths on college campuses are not from individuals who have used opioids, but from individuals who unknowingly consumed fentanyl-contaminated drugs, such as cocaine or counterfeit Xanax. UNR’s education model directly targets this modern overdose pattern, ensuring students know that any drug can carry risk.

Despite the potential to provide easily accessible naloxone, however, the online education program available on each student’s WebCampus has only been completed by 2,500 students. Of those 2,500 students, only 300 have accessed the harm reduction kits across campus. Green thinks the disproportionate interest in training is unconventional.

“It’s actually a really big surprise that that’s where more people are interested in,” she said. “Legislation and everything else is focused on the accessibility of the medication and the test strips and all of the prevention tools, right? But they haven’t focused on the training. That seems to be where the interest is. And so you can kind of see that disconnect between what people think is valuable versus what people are actually accessing.”

Without students accessing the naloxone, however, the prevention of overdose on and off campus relies on students privately accessing the life-saving drug from pharmacies or other community partners. In turn, that requires that students acknowledge the need for naloxone, a realization that experts on campus aren’t seeing students make.

“When it was just the Student Health Center, the School of Public Health, and the KC, there were maybe too few spaces where students could access it and not feel like they’re coming up here and being seen as getting something, the whole thing,” Sanderson said.

That’s why the program expanded to allow the front desks in residence halls on campus to distribute kits to individuals who complete the online training. Advertising this to students has meant informing students that their certificate of completion granted by the WebCampus course allows them to pick the kit up anywhere with no questions asked.

Despite the excitement of expanding to a more accessible space, however, the naloxone is actually only readily available at two of the university’s nine residence halls. The addition of these new locations also doesn’t address the problem of stigma, or the concern that most engagement with drugs occurs off campus.

“We know that overdoses that occur on campus are minimal, we don’t see that happening within our dorms as much,” Green said. “Most of the engagement is off campus, private housing, any of that. We want to make sure that students have access to those tools to be able to take and go to those locations.”

From fears of being identified as drug-users to a lack of knowledge about where they can access naloxone, the student initiative required to access resources for prevention leads to gaps between education and those who need it most. Helping students take the initiative to get naloxone, let alone administer it, is not easy.

Another issue for programs on campus is saturation of the existing pool of students. According to Fred, once pools of students have access to information through training outreach, hitting those populations in the future is more difficult. People who are interested in the training and in carrying Narcan are already doing so, but reaching new students has proven to be difficult, a problem statewide policy is attempting to rectify.

A Fight for Statute Changes

Efforts on campus at UNR have been coupled with larger statewide policy efforts applicable to all Nevada System of Higher Education institutions. One effort in particular came from the work of Nevada alumni Madalyn Larson, whose work to bring harm reduction to UNR stemmed from her own experience as a college student.

“Being a student and seeing the bags of coke and seeing crazy stuff that was out there and the risks of it all. And I was like ‘why’?” she said.

Larson couldn’t believe how difficult it was to access naloxone on campus, especially when she perceived the need for it from a student perspective. When she raised the concern to others on campus, those with the ability to make the change, Larson didn’t see the response the issue needed.

“I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t readily given out like condoms are at the student center and in different places,” she said. “I wrote a letter to exemplify what was happening as a student to President Sandoval, interim Dean Cardwell, Dr. Hug-English, Nancy Roget and I was like ‘Hey, let’s get this going on at UNR.’ And President Sandoval was like ‘Hey thank you so much for your email, we’re working on this, don’t worry about it’. And I was like, ‘I’m going to worry about it’.”

The summer after graduation, Larson took those worries and turned them into action. Presenting her initiative for a naloxone network to the Nevada Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, she demanded change among the drug abuse responses of the state’s higher education institutions. That change came in the form of Assembly Bill 394 (AB394).

Presented in the 83rd session of the Nevada Legislature this spring, the bill was written in the interest of generating naloxone distribution and opioid response plans among all eight institutions within the Nevada System of Higher Education. One of its major stipulations is the encouragement of a naloxone distribution network that is readily accessible to students, something that NSHE has previously refused according to Darcy Patterson, one of the founders of Wake Up Nevada, which is a local organization that distributes Narcan to those who need it.

Common harm reduction opposition sentiments about use encouragement among students presented issues along the way, but Larson wasn’t going to let anything stand in the way of allowing students to make themselves safer.

“Public health is prevention and we have to not wait until someone dies from an overdose,” she said. “Students have already died from it. And that’s why I lit the fire.”

UNR, who started distributing the drug in August 2024, before the legislation took effect, was ahead of the game. It’s up to their next steps, however, to ensure that students are actually being reached. At other institutions like University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) and Desert Research Institute, naloxone is actively being distributed to students and faculty. At UNLV, the campus recreational center has it available with no prior training necessary. This bridges the gap between students and their available resources, some of which may be completely invisible to the average student.

“We need people to have the Naloxone in their hands to be able to use it,” Larson said. "If we have 2,000-plus students doing the training and only 300 people going to get it, there is a barrier there. That’s why I really emphasize that harm reduction goes to the people, it meets them where they’re at, it goes into their classrooms and gives them it.”

The Future of Harm Reduction

For students, the future of preventing overdose requires more than just giving students the opportunity to choose naloxone, it means bringing the naloxone to them and taking it a step further. As drug use on campus continues to grow with each enrollment class gaining in size, the impact of a program that relies on student initiative can’t reach as many students as it needs to.

With pressures from stigma surrounding drug prevention to fears about being penalized for accessing such resources, informing students about the reality of naloxone and its distribution efforts is stunted by how much information users and those who surround them have. The most recent NSHE legislation, however, aims to protect these students from any backlash.

“A really important part of this bill, as a side note, is that there’s protections for students obtaining naloxone,” she said. “There’s gonna be no disciplinary action for obtaining it or using it in good faith.”

Many students aren’t aware of this, but constant advertisement of resources can help. By encouraging students to get involved with harm reduction education early, advocates hope to set up future Nevadans for success. Understanding what prevention looks like among college students who regularly use substances can aid in providing stakeholders across the state with the insight to inform future harm reduction efforts.

“If we can go upstream and really educate now and change the narrative and shift that, then we can affect the longer term when they turn up,” Larson said.

What that means for UNR programs right now is constant expansion to more students, which requires constant advertisement of resources and available support for students experiencing issues with substance abuse on campus. From counseling to the distribution of naloxone, the expansion of harm reduction on campus sets standards for the future of the state and its citizens, something UNR’s programs do not take lightly.

“You never know when you're going to have to use it,” Sanderson said. “It could be that grandma took three of her pills and forgot that she'd taken them and you need to use it to resuscitate her. It could be a friend that you see or somebody that you see out in public. I think the part that some students are like, well, ‘I'll never need that’. I've been a personal carrier of naloxone for five years now? Never had to use it, thank goodness. But why not?”

When it comes to the prevention of overdose, each piece of education that can be disseminated can save lives, and that starts with recognizing just how far harm reduction can reach with the proper resources and efforts.